For the past ten months, I’ve been struggling with the armature of my suspense novel, SEVEN DUDES DOC AND THE SEVEN. Before I tell you about my struggles, let’s define armature. And since I can’t say it any better than my friend and teacher, Brian McDonald, I’m going to let him tell you what it is.

…the armature is the idea upon which we hang our story…It is what you want to say with your piece…the armature is your point. Your story is sculpted around this point.

— Brian McDonald

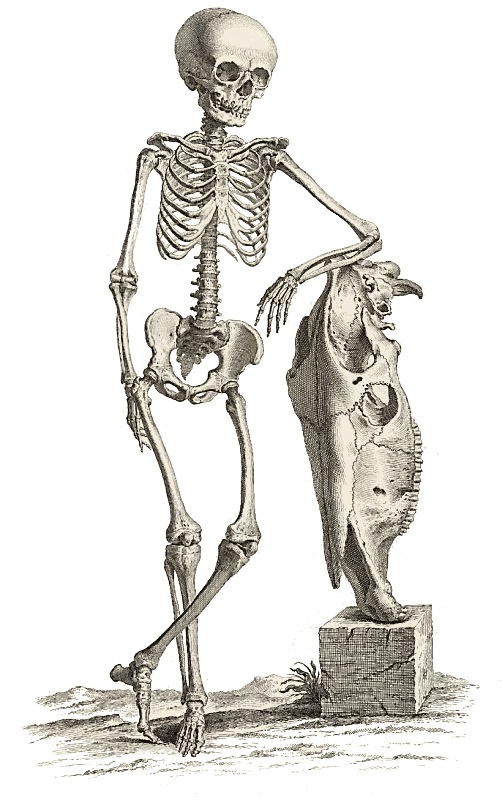

I like to think of the armature as the “spine” or “skeleton” of my story. My characters and plot are the flesh, but they’re held together by the armature.

Some people call the armature the “moral of the story.” But it’s not always a “moral” per se. Like Brian said, it’s the point you want to make. Also, it’s a sentence, not a word.

Brian explains armature very well in his book, Invisible Ink. It’s my favorite book on writing. I highly recommend you read it to learn more about armature, and to understand the key principals for building great stories.

In his book, Brian gives great examples of armatures in popular movies. Let’s look at an example of an armature in a movie you’ve probably seen more than once: The Wizard of Oz. In The Wizard of Oz, many people think the armature is, “There’s no place like home.” That’s what Dorothy keeps saying in the movie. But is it really the main point of the story? I never thought so. It never felt quite right. It wasn’t until I read Invisible Ink that I figured it out. The more accurate armature for The Wizard of Oz is: “You may already have what you are looking for.”

Look how this point is dramatized throughout the movie with each of the key characters: Dorothy, the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, and the Cowardly Lion. For example, the Scarecrow is looking for brains but he is the one that comes up with a plan or solution whenever one is needed. It happens over and over. He already has what he’s looking for. Watch the movie again. I think you’ll be amazed, just as I was, at the incredible amounts of invisible ink written into the story to prove the armature.

Which brings me to why I’m struggling.

Armature cannot just be inserted at the beginning and at the end of the story. It has to be woven into, and proven throughout, the whole story. That means, in every scene, you have to ask yourself, how am I proving or not proving the armature here?

Sound easy?

It’s not.

It took me months to figure out the armature for SEVEN DUDES DOC AND THE SEVEN before I started writing. I brainstormed armatures that seemed to go with my story, but none of them felt quite right. Finally, I chose the one that kept popping up for me and started writing. Nine months later, I finished my first draft but could tell before it was over that my story didn’t prove the armature. The armature I had chosen wasn’t right for my story.

Disappointed, but not beaten, I thought, that’s okay, I’ll write the second draft with a new armature. After spending weeks rewriting the first act, I knew I still didn’t have it. The new armature wasn’t right either.

Just last week, I changed the armature again. I think I have it this time. It seems so obvious now. I don’t know why I didn’t see it before.

So, now, I’m starting over on page one. I’m rewriting every chapter to prove the armature. If the chapter no longer works with the new armature, it’s out. And then I’ll write a new one. I already know there’s a ton of chapters that have to be completely written from scratch. This process is extremely hard and nerve-wracking, but I know it’s the right path.

I want my story to sing. I want it to be one that stays with you for days, weeks, years, and is something you will want to read more than once. I know my story won’t do that if it has no armature. All great stories have an armature that is proven throughout, from beginning to end.

Instead of rushing myself on a timeline that only makes sense to me and my anxious nature to get things done, I’m going to take time with this and make sure that every single scene makes sense to the story and proves the armature.

It’s going to be some deep diving for the next few months. Wish me luck!

Peg Cheng is the author of The Contenders, a middle-grade novel centered on the question, can enemies become friends? She is currently writing another novel that is a re-imagining of the Snow White fairy tale set in 1980s Seattle.

Okay, good luck! But you have, as you’ve noted, tenaciousness, which will probably generate the luck you need. (Forget Tenacious D, we got Tenacious P!)

I’ve gone through that on a smaller scale with poems. Sometimes I think it’s there, I tell myself it’s there, but it isn’t, really. When (and if) it finally arrives, when the last puzzle piece snaps into place, I can see that before I was just hoping. Good on you for not being satisfied with “good enough.”

Ha ha! Thanks, Edgy! That was one of my nicknames when I worked at the UW: Tenacious P. 😀

It is like a puzzle piece. I only wish I had found the right puzzle piece prior to writing 51,000+ words on my first draft. Dang! But sometimes, I can’t find the gold until I excavate the entire mine. I wish it wasn’t that way but it’s just that way for me sometimes. That is why people are always saying you have to enjoy the process of writing, rather than just the final product. I’m still trying to do that. Keep writing your poems, Edgy, and I’ll keep writing my stories.